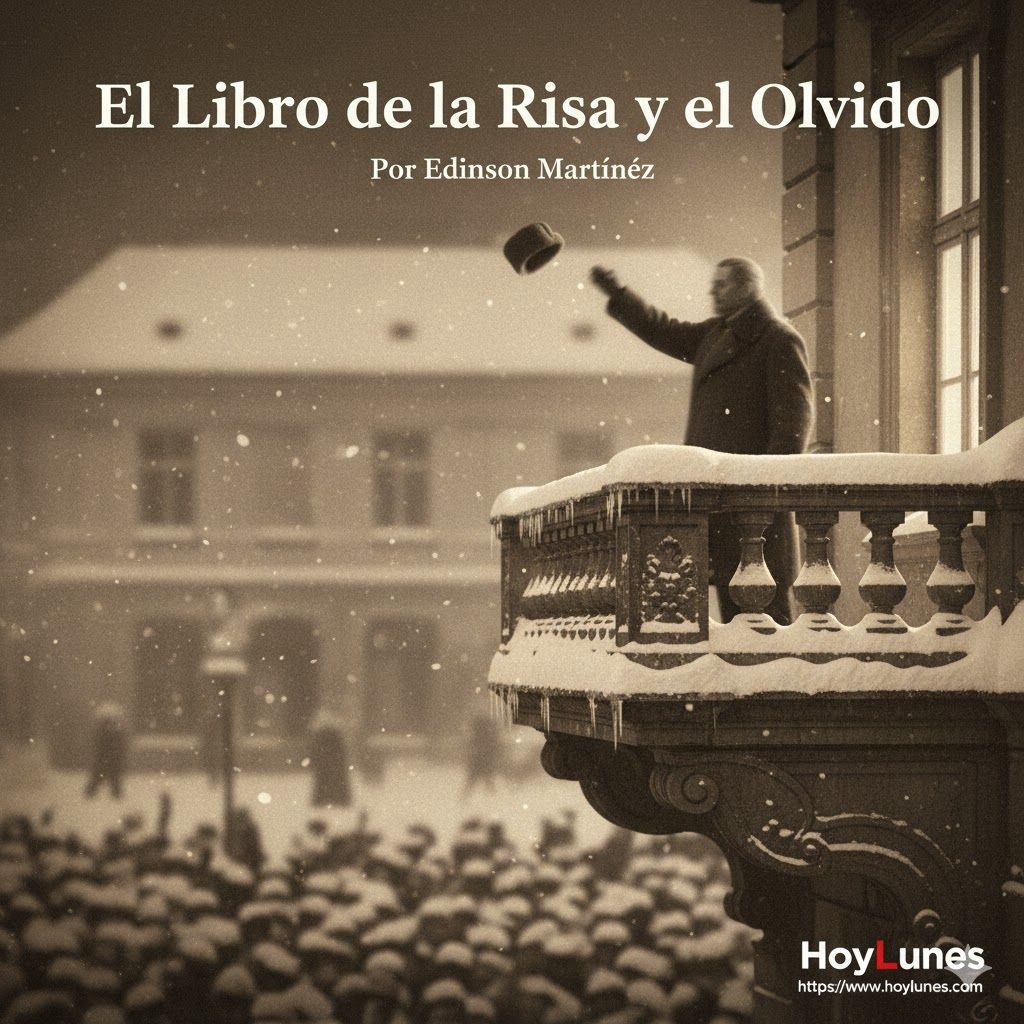

From the balcony to oblivion: power, memory, and laughter as trenches against manipulation.

By Edinson Martínez

HoyLunes – “In February 1948, the communist leader Klement Gottwald stepped out onto the balcony of a baroque palace in Prague to address the hundreds of thousands of people crowding the Old Town Square.”

Thus begin the opening lines of “The Book of Laughter and Forgetting” by Milan Kundera, a work for which, upon its publication in 1979, he was accused of treason and stripped of his nationality.

There is an absurdly easy—and equally ridiculous—tendency in all authoritarian regimes to label as foreign agents and traitors those who oppose them. Having been practiced so often, it became a tragedy of colossal proportions, the most expedient way to destroy any political debate—not through argument, but through the artificial disqualification of dissenting voices, erasing them from the stage.

Over time, it turned into a kind of script for the exercise of power from above. Though it is stupidly simple—so much so that several writers, such as Sergio Ramírez and Gioconda Belli in Nicaragua, have been stripped of their nationality because of it—it continues to be used systematically as a political weapon. It has destroyed countless lives throughout history and across nations.

Beyond arbitrary rule, such madness is always accompanied by massive manipulation of collective consciousness, by grotesque alienation among the less analytically sharp majority—mobilized by a sense of patriotism built around a heroic but entirely deceptive cause.

The same trick, once employed by communists, was also used by Nazis, fascists, and our own tropical autocrats, leaving humanity with horrifying legacies of persecution and death wherever such misfortune has taken root.

“Gottwald was surrounded by his comrades, and right beside him stood Clementis. Snow was swirling; it was cold, and Gottwald’s head was bare. Clementis, ever attentive, took off his fur hat and placed it on Gottwald’s head. The propaganda department distributed hundreds of thousands of copies of the photograph of the balcony, from which Gottwald—wearing the fur hat and flanked by his comrades—was addressing the nation.

Every child knew that photograph; it appeared on propaganda posters, in school textbooks, and in museums”.

Milan Kundera, The Book of Laughter and Forgetting (1979)

If we were to sketch the stereotype of an autocrat, among the traits we’d include is this: all of them have had a balcony from which to speak to the people—from Mussolini to Perón.

All have believed themselves essential to a higher, transcendent destiny—chosen to lead the masses toward some predestined mission. It is the “process” they invoke, as though it were the repository of all redemptive virtues. Yet one must ask: what kind of “process” depends entirely on a single head?

Here emerges, from the depths of the laboratories of official manipulation, the so-called “cult of personality”—a term coined by the left itself and used widely after Stalin, when the perversion of turning personal whims into state policy was denounced. It is the myth that gradually seeps into the collective unconscious, bearing the face and name of the leader—the alpha and omega of that ideological sect responsible for widespread derangement, subjugating society through persecution and deceit.

Only the naïve could believe that a single individual replacing the institutional name of a democratic office is not just another version of an autocrat; that indefinite reelections in public office do not ultimately corrupt the idea of democratic institutionalism. In essence, they form the cornerstone of a rebranded autocracy for the twenty-first century.

Such pretensions may be dressed up in grandiose words—historical struggles, heroic epics, proclamations of justice and social redemption—but at their core, the truth is nothing more than the endless exercise of power, for as long as the body can endure it.

There is nothing new in either national or world history. Juan Vicente Gómez, as we recall, remained in power until his death, often manipulating the constitution to extend his rule. Pérez Jiménez, though he failed to achieve the same, made no secret of his intentions. In “Habla el General” (1983),

Agustín Blanco Muñoz quotes him as saying during a long interview:

“I’ve never been bothered by being called a dictator. So far, I haven’t seen in human history a dictator who could be considered a fool…”

In Spain, the Caudillo Francisco Franco departed this world from the Palacio de El Pardo, after nearly forty years in power. Communist hierarchs, for the most part, ruled until their deaths—from Mao to Brezhnev, passing through Marshal Josip Broz Tito in the former Yugoslavia, to Fidel Castro, who remained in government until his body could no longer endure it. And in his place… he left his brother.

“Four years later, Clementis was accused of treason and hanged. The propaganda department immediately erased him from history—and, of course, from every photograph.”

Milan Kundera, The Book of Laughter and Forgetting (1979).

#hoylunes, #edinson_martínez,